‘Sometimes I look at my work and can’t believe I did it,” says photographer Neil Kenlock. “I was just doing something to stop this harsh racism that we were going through. Those images were taken so people could learn. It was very important because if I had not done that, people would say it didn’t happen.”

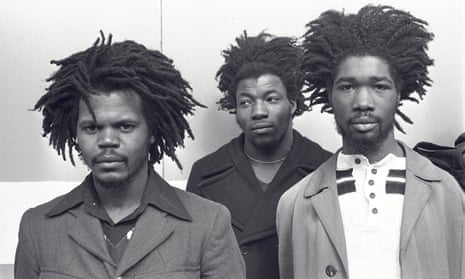

Kenlock is talking about a new exhibition of his work at the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton, London. Titled Expectations: the Untold Story of Black British Community Leaders in the 60s and 70s, it documents the struggles and hopes of the Windrush generation – postwar immigrants to the UK from Africa and Jamaica. Comprised of 25 images from Kenlock’s thousands-strong archive, these breathtaking portraits and reportage images provide a unique insight into the lives and experiences of the first generation of African and Caribbean leaders who settled in the UK and shaped the future for black Brits over two transformative decades.

These are pictures from the frontline of the black British experience. Kenlock was born in Port Antonio, Jamaica, where he lived with his grandmother until 1963, when he made his journey to England 14 years after his parents. “Every Jamaican wanted to come to Britain in those days because they thought it was where all things were great and fantastic,” he remembers. “My expectations were that I’d have a big house.”

Living in Brixton with his parents and five siblings turned out to be somewhat different. “When I arrived to see our terrace house I was shocked. I thought, ‘Is this it?’ Then I went around the back garden and it was even worse.”

He encountered racism almost immediately. “One day I went to a club in Streatham with my friend. We got to the door and they said, ‘Sorry, you can’t come in tonight.’ But white British people were going in. So the following week I put on my suit and tie and again they said, ‘No, we don’t want you here.’ I said, ‘Well, I’m not going to leave this place until you let me in.’ My friend and I refused to move and they said, ‘If you don’t go then we are going to call the police.’ And they did call the police.

“I weighed up the whole thing and I thought, ‘I don’t want my parents to hear I’m arrested.’ I walked a mile back to where my parents lived, and on the way I decided to fight against racism and discrimination for the rest of my life. But I didn’t know how to do that. So some days later, in Brixton, I saw some people giving out leaflets. That was the Black Panthers.”

The radical, gun-toting, US faction of the Black Panthers were notorious around the world for their attempts to spark change for African Americans, challenge police brutality and rebel against racism, poverty and colonialism – all while militantly dressed in black berets and leather coats. The British Black Panthers, however, were different.

“The movement in the UK was about educating people,” Kenlock says. “They were the first to understand the system, capitalism and how people looked at racism and discrimination.”

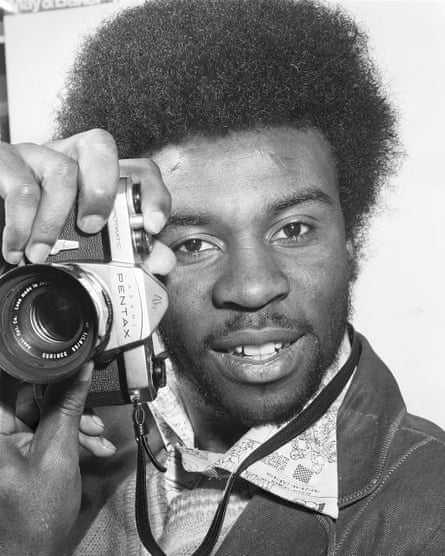

He had already developed a passion for photography. “I was working in the West End and I saw a guy on the television, and they were saying he photographed famous people and his name was David Bailey. I said to myself, ‘I want to be like him,’ but I didn’t know how to do it.

“So I got a camera and started taking pictures, but the images of black people I was seeing were not up to standard. They had no charisma, no strength. I decided then that I would never photograph anyone I didn’t see strength and determination in.”

Strength and determination were not qualities lacking in the British Black Panthers. Kenlock became their official photographer, documenting meetings, campaigns, marches and their involvement in the local black community.

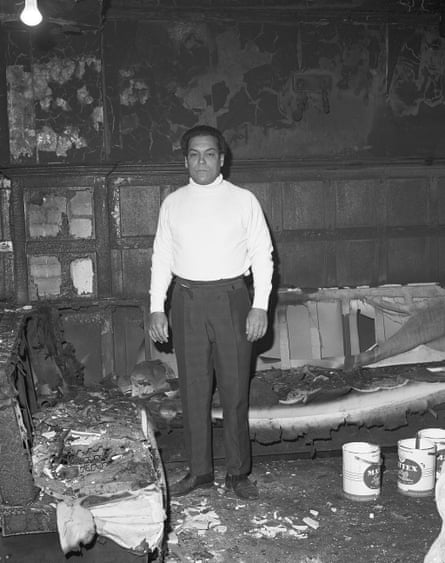

“One of the most shocking photographs I’ve taken was of George Berry, who was the first black pub owner in Brixton. He spent a fortune reinventing his pub and then he left and went home. The following morning, it was totally burned out.” Kenlock believes racists were responsible.As well as depicting the anger and fear of the time, the exhibition pays tribute to black community leaders such as activist Darcus Howe and poet Linton Kwesi Johnson, and the change they managed to effect.

“When we think of black leaders sometimes we don’t see them as individuals, but they are all very different,” says Emelia Kenlock, Neil’s daughter and curator of the exhibition. “All the images include challenges that the leaders would have had, changes that they would have needed to make and most importantly collaboration – because while there’s an element of loneliness in leadership, they all collaborated at some point to magnify their message.”

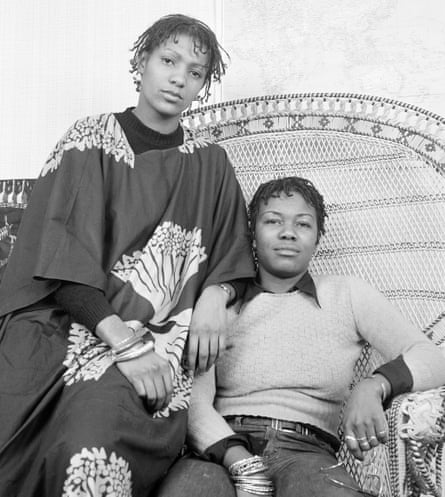

One such image depicts Olive Morris and Elizabeth Obi, photographed in 1973, sitting on the kind of wicker chair US Black Panther co-founder Huey Newton would have posed on. Morris, who died of cancer aged 27, was an anti-discrimination, women’s and squatters’ activist and one of the key members of the British Black Panthers. Obi worked closely with her, both in the Panthers and in founding the Brixton Black Women’s Group, and the image captures the camaraderie between these pioneering young women.

Kenlock remembers Morris “one cold winter day in Brixton – she was squatting in a flat. The police and the bailiff came to evict her and almost 100 people gathered around the building to support her. The police agreed there was no way they could evict her that day and they left. I went up to her flat and she was cold and warming herself up. She stood up there and told everybody thank you.”

As well as reflecting racism and struggle, the exhibition also provides an opportunity for Kenlock to reflect on the people and places who provided “some of the best times of my life”.

“I remember photographing Darcus Howe many times – we were very close,” Kenlock says of the Trinidadian writer, broadcaster and activist, who died in 2017. “He was pragmatic, friendly, but very serious about discrimination. He was a giant – you could see him marching around with his brother.”

In 1971, Howe was one of the Mangrove Nine arrested after a protest in Notting Hill, London, against the continual police raiding of a restaurant used by black activists turned violent. “He was charged with riot, affray and assault and could have got 20 years in jail,” says Kenlock.

Howe defended himself at the Old Bailey and won the case, which made legal history for being the first judicial acknowledgment of “evidence of racial hatred in the Metropolitan Police”, according to the George Padmore Institute. “Judge Argyle wasn’t happy about Darcus defending himself, but Darcus came up with some very good arguments – and he won. It was an important case because they wanted to imprison everyone in the Black Panther movement and, unfortunately for them, it didn’t work out.”

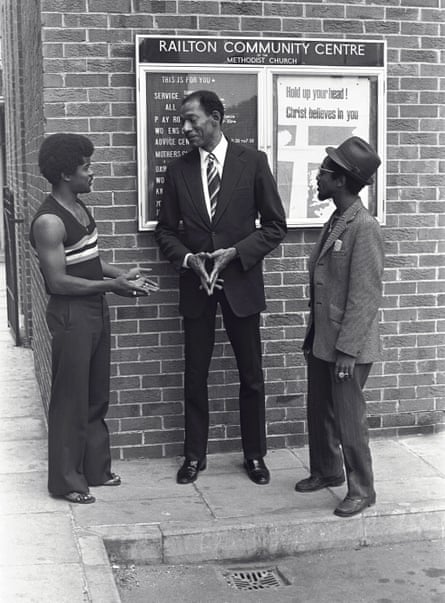

Other prominent figures in the exhibition include Steve Barnard, the first black BBC radio presenter with a reggae show; and Arthur Stanley Wint. The Jamaica high commissioner from 1974-78, the deeply impressive Wint had also been the first Jamaican Olympic gold medallist, anRAF pilot and a surgeon.

“He didn’t behave like a regular high Commissioner – he wasn’t stuffy, he was very pleasant. I think he liked me,” Kenlock says with a chuckle. “One time there was a riot in Brixton and he came out to speak to young teenagers, pacifying them and telling them they needed to go to university. I always remember that because it showed how caring he was. Some high commissioners didn’t bother to come, but he drove down from Grosvenor Square and met with the community.”

Memories like these testify to the tumultuous times the British Black Panthers experienced. Kenlock has been at the forefront of the progress made by Britain’s black community, working as a photographer at community newspaper West Indian World, launching the first black British glossy magazine Root and co-founding Choice FM – Britain’s first 24-hour black music radio station with a licence. He is embedded throughout black British history and culture.

One of Kenlock’s favourite images in the show is that of a young woman pointing at “Keep Britain white” graffiti. Like the exhibition as a whole, it expresses pride and dignity in the face of oppression, a refusal to accept discrimination and the resilience to overcome it. It’s a show about the past, but with an eye on the future. As Kenlock concludes: “I want people to see my work and be inspired and I want them to know that they can do it, too.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion