At the Iowa Democratic party’s Hall of Fame dinner, in June, Washington governor Jay Inslee told a room of activists nibbling crab rangoon and meatballs about his distant family connections to the state – and his newfound love for it too.

Two years out from a presidential election, in the state that holds the first nominating contests, such events were once the norm. In 2002 and 2006, midterm years under a Republican president with no frontrunner to challenge him brought Democratic hopefuls flocking to the Hawkeye state.

In 2002, the top Democrats in the House and the Senate, the previous vice-presidential pick and a handful of senators and governors all took the flight out to Des Moines in the summer months.

In 2006, John Kerry and John Edwards, the party’s ticket from two years before, worked dinners and speeches separately, even campaigning for the same state Senate candidate two weeks apart. Three other sitting senators showed up.

Democrats now anticipate the most wide-open presidential field in modern history. But in Iowa, presidential hopefuls have been slow to show. Few bold-faced party names have appeared, leaving campaigning in the state mostly to backbench congressmen and other underdog candidates.

Twelve years ago Rob Sand, the Democratic nominee for state auditor, managed a statewide campaign. “It may still be too early to tell comparatively if there is less involvement,” he said of 2018, though he did remember that there were “definitely more presidential aspirants being present and assisting candidates in 2006”.

Things were different then. For example, candidates could not tweet to their followers about campaign stops. Twitter had not been invented; nor had the smart phone. Something else had not been invented: a Trump presidency.

Donald Trump has broadened the focus of the entire Democratic party, away from single candidates seeking the limelight and towards a sort of collective pushback. As one operative who works for a Democrat mooted as a 2020 candidate put it: “If you’re out there promoting yourself and doing things only beneficial to you, you’re actively doing a disservice to yourself.

“There has to be the right balance of showing up in early states and delivering results. It can’t be about you and it has to be about promoting the Democratic party and helping to find message.”

Several more local factors may have helped keep Democratic contenders away. The first was a gubernatorial primary that was expected to be competitive enough on its own. The second is Iowa’s unique campaign finance disclosure timeline. Any contributions made after 15 July will not need to be disclosed until only two weeks before the elections in November, making later visits attractive. Thirdly, Iowa’s own legislature is no longer closely balanced, as it was in 2006. Both chambers are controlled by the Republicans, making state races far less a priority for either national party.

The pace is starting to pick up a little. In the coming weeks, Senator Jeff Merkley of Oregon, Governor Steve Bullock of Montana and congressman Tim Ryan of Ohio are expected to visit again.

The impact of such possible presidential candidates is not simply measured by how many hands they shake at county fundraisers or how many television ads they air. In 2006, potential candidates embedded staff on state campaigns. Evan Bayh and Russ Feingold placed staffers, paid by their political action committees, in key races. The Edwards campaign in waiting played an important role in support of Chet Culver’s successful run for governor.

This year, the most notable public expenditure by a national figure has been an in-kind donation of office space from Jason Kander’s organization, Let America Vote, to Sand, the Democratic nominee for auditor. Kander, formerly secretary of state in Missouri, recently announced he would run for mayor of Kansas City, dropping any potential national ambitions. But Iowa Democrats still noted that staffers were being placed with candidates in an under-the-radar way.

One presidential hopeful has been much more active than anyone else. John Delaney, a member of Congress from Maryland, has not only formally announced his candidacy, he has crisscrossed the cornfields of Iowa. So far, he has made 12 different visits and held events in 72 of the 99 counties.

John Davis, a senior advisor to Delaney, told the Guardian: “We have made a very concerted effort to run a real caucus campaign and start early. John knew early going into this that people didn’t know who he was and [is seeking to] correct that while trying to support as many Democratic campaigns as he can.”

When the field expands to hold 15 to 20 candidates, Davis said, “talking to folks and having these meaningful conversations is how you get people to stand up and be precinct captains in 2020”.

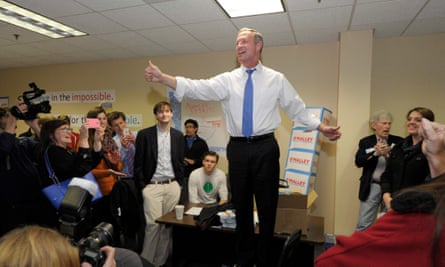

Delaney, who is funding himself, has been buying TV ads in Iowa, something no other candidate has done so early. The result is that a poll taken in the spring had his name identification among caucusgoers above 50% already. Jake Oeth, state director for Martin O’Malley in 2016, observed that the former Maryland governor never reached that level, even on caucus day after tirelessly covering the state.

Delaney’s unique approach may simply indicate that as 2020 approaches, candidates are going to experiment. Pete D’Alessandro, one of Bernie Sanders’s top strategists in Iowa in 2016, pointed out that conventional wisdom about the caucuses is that “you have to do the small event with 20 to 25 people sitting around the table”. But with Sanders, he said, “we didn’t do one of those events”.

D’Alessandro thought that in the 2020 race, there would be “half a dozen clearly divergent strategies” for how to win the state.

After all, of the potential candidates who were most active in Iowa in the summer of 2006, only John Edwards even eventually ran for White House. Hillary Clinton did not visit once while Obama only made three brief late visits in the fall. If potential 2020 candidates are looking for a new playbook, they will not be the first to do so.