Ted Landsmark’s legacy is more than a photo

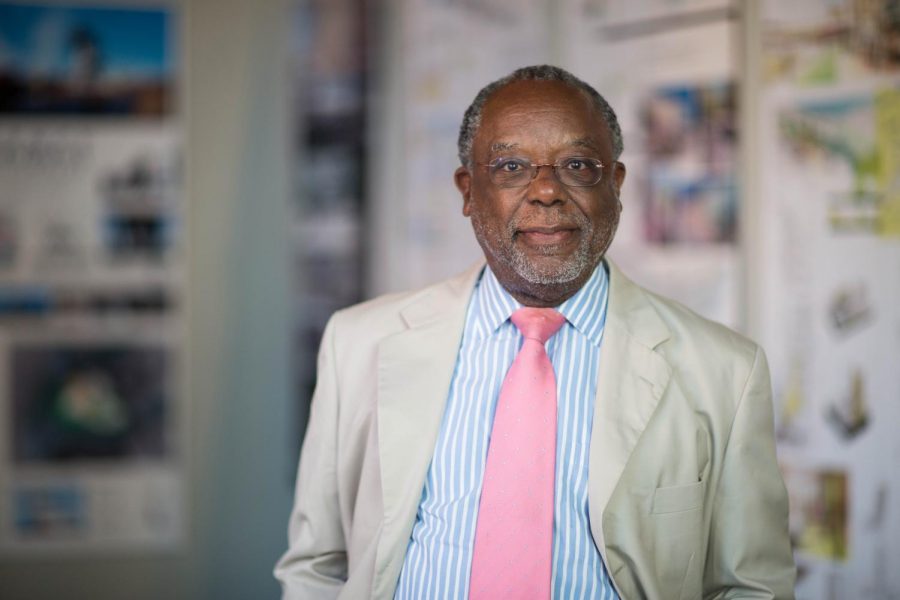

Courtesy School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs

He was attacked on his way to work 45 years ago. But now Ted Landsmark is a ‘Boston legend’ for other reasons.

March 18, 2021

Ted Landsmark is a man of many “ands” — he is the director of the Myra Kraft Open Classroom and the Kitty and Michael Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy, a Boston Development and Planning Agency board member and former president of the Boston Architectural College. He has a bachelor’s, a master’s and a law degree from Yale, a Ph.D. from Boston College and has taught across the disciplines of public policy, city planning and African American culture.

His varied interests shine on the walls of his home office, which display his collection of banjos, art and historical maps: He’s also on the board of the Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library.

“It’s difficult to wrap your head around the human that is Ted Landsmark, because he is a scholar in the truest sense of the word, and a good human in the truest sense of the words,” said Rebecca Riccio, Director of the Social Impact Lab. “He has such a vast array of academic areas of expertise.”

Despite all his achievements, some people first identify him with a photo taken 45 years ago, when he was assaulted outside City Hall by anti-busing protesters. This was in 1976, when Boston attempted to desegregate public schools.

An image of this moment, titled “The Soiling of Old Glory,” appeared on the front pages of newspapers across the country and won the 1977 Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Photography.

Landsmark was a young lawyer at the time, working with contractors from marginalized groups to obtain infrastructure deals within the city. The flagpole narrowly missed his face, but a punch from another demonstrator left him on the ground with a broken nose.

“My initial reaction was to indicate that I wasn’t angry with the young people,” he said. “But I felt that the city needed to address their having been provoked into violence by political leaders who were trying to perpetuate patterns of racism in the city.”

The attack thrusted Landsmark into the spotlight — but before and since, he dedicated his career to less-publicized issues of social justice across policy, design and higher education.

“He’s like a Boston legend,” said Hilary Sullivan, director of community service and civic engagement at Northeastern City and Community Engagement. Sullivan collaborates with Landsmark on Northeastern’s Voter Engagement Coalition. “His opinion and advice and thoughts are very sought after.”

Landsmark grew up in Harlem and was raised by a single parent in public housing. He fundraised for Freedom Riders during the Civil Rights movement and participated in the march across Selma and the 1963 March on Washington.

“I would never have gotten to Yale if I hadn’t encountered a young white seminary student who took me under his wing and said, ‘You’re a pretty smart guy, you ought to think about going to Yale,’” Landsmark said. “And I looked at him and said, ‘Yeah. And I’m going to be an astronaut too.’”

Landsmark got in, however, and he spent an extra year at a college prep school in New Hampshire before matriculating in New Haven. He said that experience was an important transition to the culture of elite higher education.

“When I was in college, if you went to an elitist New England school as I did, if you are from the South, or the Midwest, you can often feel very isolated and sometimes diminished by students who look down on you,” Landsmark said. “I was used to dealing with a wide range of white students who might otherwise have looked down on me. And when I got to Yale, I was ready for all of the elitist attitudes that I was likely to encounter.”

He recalled his freshman year roommate, who was from a small city in North Dakota.

“I settled in very comfortably. He went home after Thanksgiving and never returned to Yale, because he felt so isolated from the rest of the culture there,” Landsmark said. “Clearly, today, the same thing happens among students who arrive and who haven’t already been exposed to the Greater Boston academic culture.”

Those lessons stuck with him later in his career, when he transitioned from practicing law to becoming a professor and leader in higher education. Landsmark served as the president of Boston Architectural College, or BAC, from 1997 to 2014. The school credited him for significantly increasing the diversity of its faculty and student body and expanding its scope of degree programs.

In 2006, the American Institute of Architects honored him for his work to make the profession more inclusive of people from marginalized identities. Since then, he has continued to advocate for social justice issues both in and out of the academy.

“We need to have a learning community that recognizes people’s differences, recognizes the ethical responsibilities,” he said. “It is essential that higher education institutions recruit and provide support services for more diverse students … We need to recognize that because the world’s leadership moving forward will be much more diverse than it has been up to now.”

Landsmark was dismissed from BAC in 2014 following institutional financial struggles, but then joined Northeastern’s College of Social Sciences and Humanities, where he is now director of the Kitty and Michael Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy.

In 2014, Mayor Marty Walsh appointed him to Boston Planning and Development Agency’s five-member board, which approves all major construction projects in the city. Landsmark said during his time there, the panel has signed off on more than $50 billion in development.

At Northeastern, Landsmark is now researching voter wait times in various states in collaboration with other faculty. Last summer the group received a grant from the university to develop the Time To Vote app, which reminds people to vote and collects data on how long they wait in line.

“We’re really excited about using this technology to support voting rights advocates in their work to promote equitable allocation of electoral resources,” said Shannon Al-Wakeel, managing director of Northeastern’s Center for Public Interest Advocacy and Collaboration. “We want this smartphone app to be able to get really precise data that advocates can use to make their cases, and really identify where the biggest issues are.”

The team rolled out the app in Arizona and North Carolina during the 2020 presidential election, and later the Georgia senate runoffs. Al-Wakeel said they might also make it available to voters in the Boston mayoral primaries this fall.

Landsmark also supports student-led voter engagement with the Voter Engagement Coalition and mentors students through a range of socially-engaged capstone projects.

“Many of our students come from cultures and economic backgrounds where ethnic or racial or gender discrimination exists to a considerable extent, but it’s largely set aside as an issue that students should engage with,” he said. “This is a moment when students have the opportunity to learn from and to engage with people in the United States and elsewhere in the world, around issues of achieving social justice and equality.”