In January 2013, the documentary film-maker Laura Poitras asked Barton Gellman if he wanted to grab a coffee. The venue was New York. Poitras told Gellman – a former Washington Post reporter – that a few days earlier a mysterious source had been in touch with her.

The person claimed to be from the US spy community. He had news: the NSA or National Security Agency – America’s foremost signals intelligence outfit – had built an unprecedented surveillance machine. It was secretly hoovering up data from hundreds of millions of people. The implications were terrifying. The correspondent said he could supply documents.

This sounded promising, but how could one be sure? Over the next few months Gellman held a series of encrypted chats with this strange informant, code name Verax. Verax was sizing up Gellman for a job of historic proportions, it turned out. He was to be co-recipient of a trove of ultra-secret national security files.

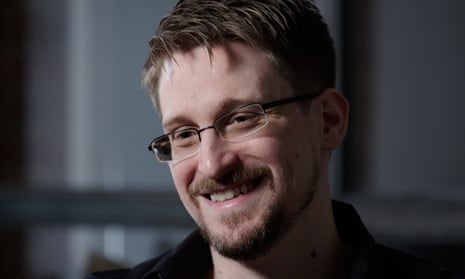

Dark Mirror is Gellman’s account of his interactions with Edward Snowden – a series of lively exchanges, fallings out and making ups. It is a fine and deeply considered portrait of the US-dominated 21st-century surveillance state. Snowden’s story has already been told in books, a film and a play. The whistleblower’s own memoir Permanent Record, written from Moscow, was published in September.

Gellman has waited seven years to give his version. He has spent the time well – delving into some of the more abstruse programmes from the Snowden archive, and talking to sources from the tech and security worlds. Dark Mirror doesn’t alter what we have known since 2013: that the NSA and its British counterpart GCHQ routinely sweep up virtually all of our communications. But it does provide new and scary technical detail. The original documents – published by the Guardian and the Washington Post – revealed that the NSA claims backdoor access into the servers of Google and other social media companies, and grabs phone records. Privacy advocates call this spying; GCHQ disagrees. Yes, it collects our metadata in bulk. But, it adds, it doesn’t examine it without proper legal cause.

Gellman argues that the NSA has gone so far as to make this distinction meaningless. The agency has constructed a live social graph of who speaks to whom. This includes not just terrorists but everybody. This database is constantly updated. And is precomputed. That means it is ready to yield up the intimacies of a person’s life “at the touch of a button”, Gellman writes – romantic, professional, political.

The dark mirror is a metaphor for the modern surveillance state: the security agencies can’t be seen, we can. This massive expansion of spying capability took place in the years after 9/11. Until Snowden came along – giving material to Poitras, Gellman and the then Guardian columnist Glenn Greenwald – citizens had no idea of the scale of this operation, or its civic implications.

The Snowden who emerges from these pages is neither a hero nor a traitor. Gellman sketches him as “fine company, funny and profane” with a “nimble mind and eclectic interests”. He can also be “stubborn, self-important and a scold”. Gellman sees his role as that of a curious journalist, rather than advocate. Snowden isn’t a Russian asset, he concludes, but may well have damaged national security – a view Snowden rejects.

The most enthralling chapters cover the race to get the story out. Gellman had left the Post in 2010 and briefly contemplated going to a different paper. There are tense meetings with Post executives and lawyers. When he tells colleagues to get rid of their mobile phones several react as if they’ve been told “to peel off their socks”.

Publication was made fraught by the fact that Snowden had left his NSA contractor job in Hawaii and fled to Hong Kong. He invited Poitras and Gellman to join him there. After agonising, Gellman decided not to go. This was the wrong call; he writes with honesty about his fear of arrest and prosecution. In June Poitras, Greenwald and the Guardian journalist Ewen MacAskill interviewed Snowden in his Hong Kong hotel room.

Gellman is frank about the pressures of taking on the Obama administration. Someone tried to hack his iPhone and laptops. He bought a safe for his New York apartment, rode the subway using burner phones. All this had a cost in terms of “time, mental energy and emotional equilibrium”, he writes.

Yet his paranoia was justified. Foreign intelligence services sought to get their hands on the leak. A Russian emailed to ask if Gellman might share a copy of the NSA’s black budget. Gellman’s colleague Ashkan Soltani received multiple approaches from “hot” young women via the dating service OKCupid; their profiles subsequently vanished. When Gellman visited Snowden in Moscow in late 2013, he took elaborate precautions.

For a while after the Snowden publications, Gellman’s top intelligence contacts snubbed him. This hostility ended once Donald Trump became president, and declared war on his own intelligence operatives.

Dark Mirror brings down the curtain with Snowden stuck in Moscow, apparently content with his lot. He is, Gellman writes, an “indoor cat”, who considers his mission accomplished. There is little prospect of Snowden returning to the US, where he faces espionage charges. The most consequential whistleblower of our times does not regret his costly moment of truth-telling.