When a political opponent speaks, we should listen. Many college campuses offer students and other interested parties an opportunity to listen, but they are often thwarted by those who don't want them to hear.

Colleges are the best place to exchange and explore ideas, foster opinions to help change another's mind or persuade another, or to have a deep discussion and develop thoughts about an intellectual principle. An academic environment is not a place for anger or controversy.

In colleges, it's one idea vs. another idea — perhaps a political opponent can convince one away from one's ideas and philosophy. At least open-minded people can respectfully disagree.

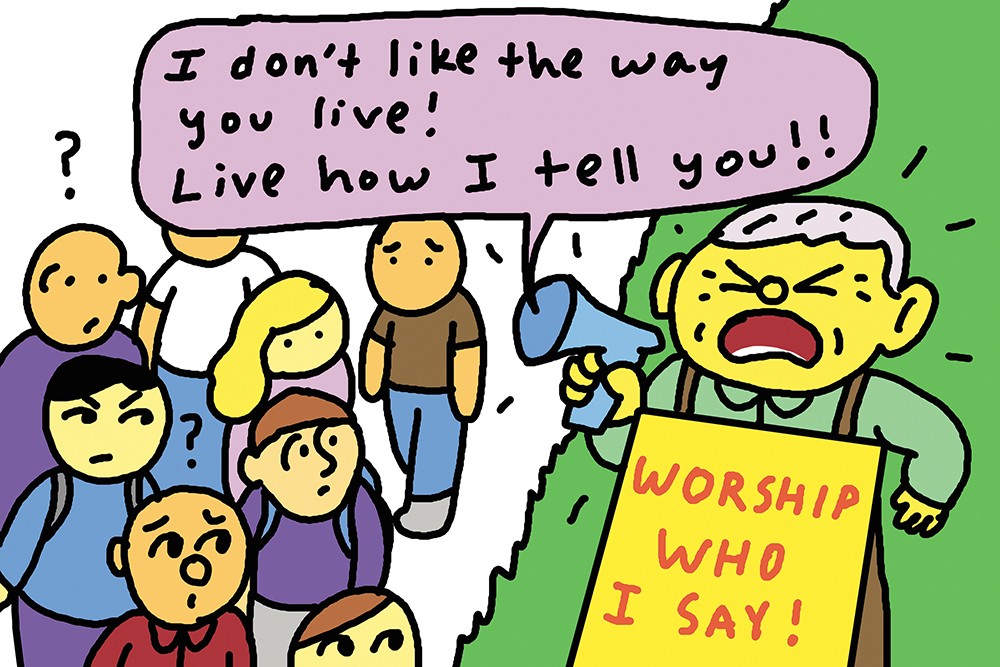

But if we're prevented from even learning from each other because some third party, intolerant of another's opinion, wants to stop anyone from learning, that destroys the purpose of any college.

Too often, college professors, deans or other radical students are the prime movers behind preventing the learning process from occurring; instead shutting down a person with opposing views, having a speaker's college invitation revoked or creating such a ruckus that the person with opposing views is unable to speak.

Lately, conservative expressions have been demonstrated against. The University of California at Berkeley recently shut down a conservative speaker, preventing her from sharing even one idea or thought. Liberal, intolerant students objected to her speaking. Some professors may have been involved — it's happened before. Demonstrations ensued. Not wanting to be injured, attendance dissipated and the conservative's ideas were not heard. A blow was therefore struck against intellectual curiosity.

American courts have gotten involved in this issue, too. The 4th Circuit Court of Appeals in Vista Graphics, Inc. v. the Virginia Department of Transportation held that the government, if it displayed government-created brochures at rest stops, was responsible and therefore such brochures constitute government speech, comporting with prior Supreme Court decisions. The rulings invoke an evolving "government speech" doctrine, holding that the government could silence expression and wasn't obligated to display private brochures it didn't like. This gives public universities thin cover for barring speech; private schools, meanwhile, can decide for themselves.

Our Constitution, however, in the Bill of Rights promises that everyone in America has the right to express information, ideas and opinions free of government restrictions based on content and subject only to reasonable limitations especially as guaranteed by the First and Fourteenth amendments to the Constitution. Essentially, any American can speak their mind as they see fit (except in such cases as yelling "fire" in a crowded theater, for example).

One humid June day in Washington, D.C., I recall four visiting Future Farmers of America mentioned they had seen a man dressed in a heavy, wool garment, holding a Bible and shouting scripture loudly. The surprised students were told that, no matter how annoying he was, the man was only exercising his rights.

Free speech should always remain free, no matter how uncomfortable it may make us. But a recent Knight Foundation report found students are split on the matter, with 53 percent of those polled favoring the First Amendment guarantee to speak freely and disagree, while 46 percent prefer to promote inclusion on campus to absolute free speech. Fifty-eight percent said free speech should protect hate speech, while 41 percent disagreed.

The editorial page of the Wall Street Journal recently mentioned that George Washington University is being pressured to abandon the mascot name "Colonials," held since 1926, in favor of a less controversial name, all in the name of political correctness. Fifty-four percent of the students there favored the name change. The trustees should hold firm — for free speech.

The First Amendment remains sacrosanct in constitutional history, and free speech, especially on college campuses, should always be protected so that speakers of all kinds can express themselves. ♦

George Nethercutt represented the 5th District of Washington in Congress from 1995-2005.