Alayiah Ray's public school is her safe haven, a place where people of all stripes are free to be themselves, together.

“We're very open to all personalities and all religious backgrounds, racial backgrounds, all of that,” said Ray, an 11th grader at Benjamin Franklin High School in New Orleans.

So she was alarmed this week when Louisiana’s House of Representatives passed a bill requiring public K-12 schools — along with universities, charter schools and private schools that receive public money — to post the Ten Commandments in every classroom. The measure felt contrary to the ethos of acceptance at her school and in the country’s founding principles.

“I feel like they're saying, 'Here in America, this is what we believe,’’ Ray said, “and if you don't believe in this, you're an outsider and you don't really fit in here.'”

Alayiah Ray, left, and Camerin Aguillard are 11th grade students at Benjamin Franklin High School in New Orleans.

The legislation comes as conservative lawmakers across the country seek to inject religion and spirituality into public schools, piercing the traditional barrier between church and state. Along with requiring the Ten Commandments to be displayed, other proposals in Republican-led states have included bringing chaplains into public schools, allowing elective courses on the Bible and freeing teachers to pray in front of students.

Many of the same lawmakers also want to rid classrooms of content that they say contradicts Christian values. In Louisiana, Rep. Dodie Horton, R-Haughton, who sponsored the Ten Commandments bill, also authored a bill that would prohibit classroom discussions about LGBTQ+ issues or other topics related to sexuality and gender. The aim, Horton said, is to ward against “inappropriate influence and intrusion.”

But, to critics, forcing schools to post a Biblical text on classroom walls is a glaring example of inappropriate influence.

The Ten Commandments bill “is essentially government-sponsored religious messages imposed on captive audiences — students who have to be at school day in and day out,” said A’Niya Robinson, advocacy strategist for ACLU of Louisiana.

That bill and another the Louisiana House passed Wednesday, to let schools hire chaplains, follow recent U.S. Supreme Court rulings that signal an openness to reexamining the church-state divide. However, critics argue that the Ten Commandments bill remains clearly unconstitutional, and some free speech groups already are threatening legal action if the bill becomes law.

“This is too egregious not to litigate,” said Annie Laurie Gaylor, co-president of the Freedom From Religion Foundation. “We do not put Biblical edicts in our secular public schools that are supported by taxpayers of every religion or no religion.”

Displaying ‘God’s law’ in schools pushes legal limits

A precursor to Louisiana’s bill was found unconstitutional more than 40 years ago.

In 1980, the Supreme Court struck down a Kentucky law requiring public schools to post the Ten Commandments in classrooms. The majority ruled in Stone v. Graham that the law violated the First Amendment, which prohibits the government from “establishing” a religion.

The court relied on an earlier case, Lemon v. Kurtzman, that said a law must have a primarily secular purpose to avoid running afoul of the First Amendment’s establishment clause. The Kentucky bill failed the so-called Lemon test, the court ruled.

“The preeminent purpose for posting the Ten Commandments on schoolroom walls is plainly religious in nature,” the majority wrote, adding that the law would "induce the schoolchildren to read, meditate upon, perhaps to venerate and obey, the Commandments.”

But, in 2022, the court’s new conservative supermajority scrapped the Lemon test. In Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, which upheld a football coach’s right to pray on the field, the court said the test of whether a law violates the First Amendment is whether it’s consistent with the country’s history and traditions.

“That puts all of those cases decided under Lemon up in the air,” said Lea Patterson, senior counsel at First Liberty Institute, a legal group that promotes religious freedom.

It’s not clear that Louisiana’s bill would pass the new First Amendment test, as public schools have not traditionally posted the Ten Commandments.

Legal experts also noted that the Kennedy case involved a coach praying outside of school without requiring players to join, while putting the Ten Commandments in classrooms could be seen as the state foisting religious beliefs on students.

“The Kennedy decision does not in any way, shape or form allow schools to now go about endorsing religion or coercing students to participate in religious exercise,” said Nik Nartowicz, state policy counsel at Americans United for Separation of Church and State.

The bill’s supporters argue that it does not promote a particular religion.

“The Ten Commandments are universal,” said Rep. Mike Bayham, R-Chalmette. “It’s something that cuts beyond sectarian faiths.”

Yet during the House debate on her bill, Horton appeared to acknowledge the text’s Judeo-Christian roots.

“I’m not concerned with an atheist. I’m not concerned with a Muslim,” she said when asked about teachers who might not subscribe to the Ten Commandments. “I’m concerned with our children looking and seeing what God’s law is.”

Students fear loss of ‘safe spaces’

If Horton’s bill is signed into law, it almost certainly will face legal challenges. In the meantime, schools will be tasked with carrying it out.

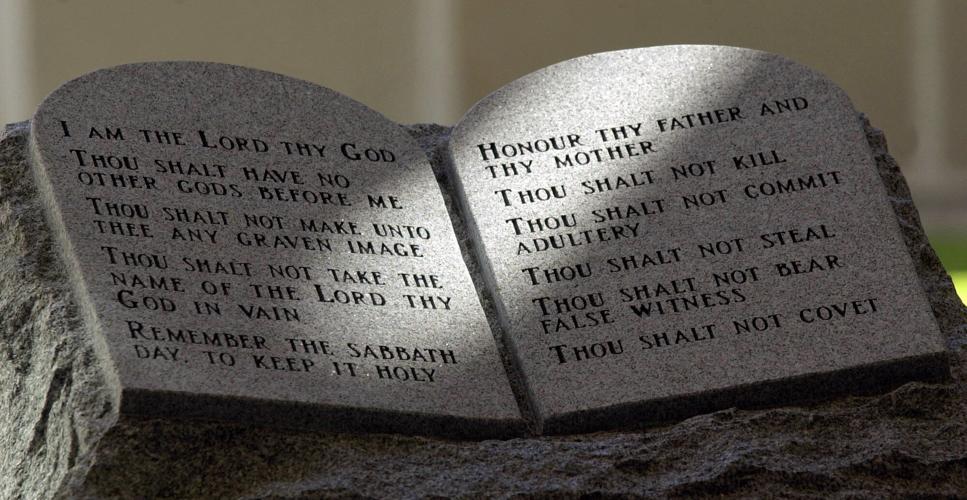

The measure, House Bill 71, allows schools and colleges to pay for Ten Commandments posters or accept donated ones. The displays must be at least 11x14 inches with "large, easily readable” font.

Teachers would have to navigate potentially sensitive questions about the text, whose exact wording is spelled out in the bill.

For example, one of the edicts is: “Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor's wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his cattle, nor anything that is thy neighbor's.” Another: “Thou shalt not commit adultery.”

Some critics questioned whether the text would comply with Horton’s other bill, which prohibits classrooms discussion about sexual orientation or gender identity.

“Would I be fired for explaining what adultery is even though I’m required to have the word ‘adultery’ on my wall?” asked Jacob Newsom, social studies teacher at St. Amant High School, a public school in Ascension Parish. “That seems like a lawsuit waiting to happen.”

Critics also questioned why the state would devote resources to the bill — which could include defending it in court — when schools have more pressing needs.

Many students are struggling at home and school “and we think that what they need is a laminated piece of paper with the Ten Commandments on it?” Newsom asked. “It just seems ridiculous, with all the issues we have in the public schools, that this is what we’re debating.”

Back at Franklin High School, students were already imagining what it would be like to walk into a classroom and see the Ten Commandments hanging on the wall.

“I would feel uncomfortable,” said 11th-grader Camerin Aguillard. She also fears where the law would lead. “It opens the door to more implementation of religion in public schools, which defeats the purpose of attending a public school.”

Ray, her classmate, considered Rep. Horton’s dual efforts to require students read the Ten Commandments and forbid them from discussing aspects of their identity.

“It's slowly chipping away,” she said, “at the safe spaces that students used to have in classrooms.”

Staff writer Elyse Carmosino contributed reporting.